Establishment:

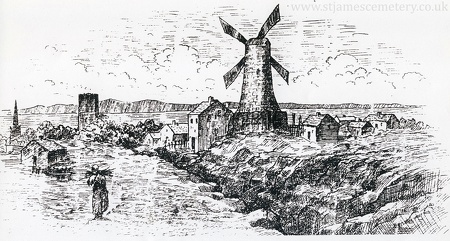

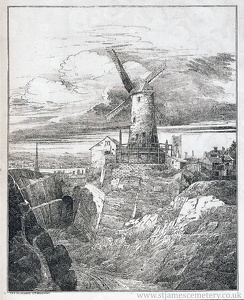

In August 1825, a meeting was held at Liverpool Town Hall to discuss the necessity of a new public cemetery in Liverpool. The non-conformist Liverpool Necropolis (also known as Low Hill Cemetery) had opened in February 1825 on the two-hectare site at the corner of Everton Road and West Derby Road. It became apparent that an aflternative cemetery was desired, this being in affiliation with the Church of England. Such a cemetery “should be on a plan similar to those on the Continent of Europe, in which perfect security, simplicity of ornament, and retirement of situation are happily combined” (St James’ Cemetery Trustees 1825). It was intended that 1,500 shares of £10 each were to be sold to raise funds for the construction of the new cemetery. John Foster Junior was appointed as architect, along with John Shepherd of the Botanic Gardens as landscaper, both of whom had worked together on Liverpool Necropolis. In September 1825, the site of a former stone quarry was chosen for the new cemetery, bounded by Duke Street to the north, Upper Parliament Street to the south, Hope Street to the east, and St James’ Mount (previously Quarry Hill and Mount Zion) to the west. The quarry had provided material for the construction of the Old Dock (opened in 1715), the Town Hall, and several other public buildings, but had been exhausted by 1825.

Read more about the quarry and St James' Mount

Foster presented his plans for the new cemetery comprising of 44,000 square yards (3.7 hectares) in October 1825. An Act of Parliament was passed on May 5th 1826 formalising the provision of the additional cemetery and allowing the borrowing of up to £20,000 for construction. It enacted other regulations with regard to appointment and duties of officials, as well as banning the burial of any corpse nearer than two feet to the ground’s surface (St James’ Cemetery Act 1826).

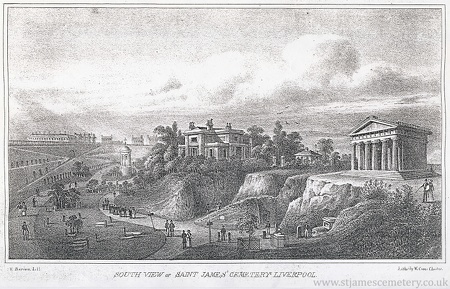

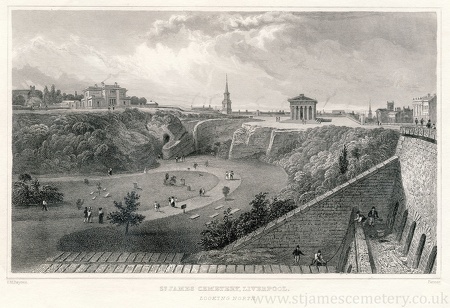

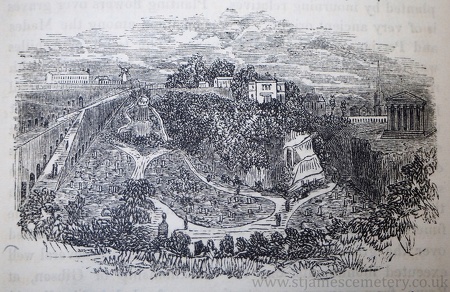

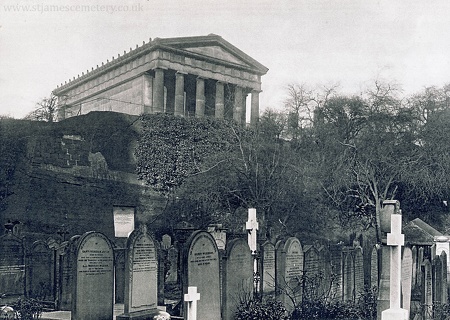

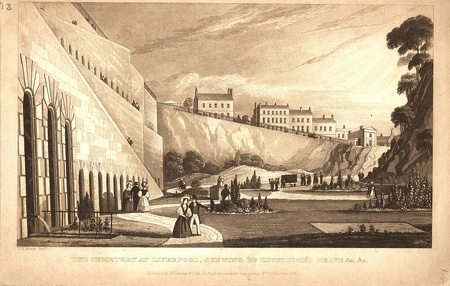

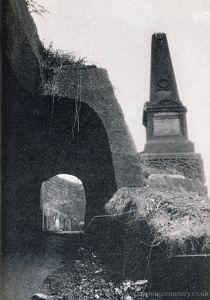

Construction of the cemetery began in August 1827. The site was enclosed by stone walls and iron railings, and four entrances with gates led into the cemetery; two from Duke Street, one from Hope Street, and one with a monumental archway at the south end of St James’ Walk. The eastern wall, almost perpendicular, was 52 feet (15.8m) high and 1,100 feet (335m) long and included broad ramps lined with a total of 105 catacombs cut into the rock face. The ramps allowed for the procession of funeral carriages down into the cemetery itself, and were protected by walls approximately two and a half feet in height (76cm). The lower ground of the cemetery itself was laid out with winding paths lined with trees and shrubbery. The mortuary chapel was designed in the Greek Revival style, with a portico with six fluted columns at each end. It was situated prominently on the higher ground to the north-west where the quarry’s windmill had been located, accessed from the cemetery grounds by a small subterranean tunnel through the rock. The minister’s house was positioned nearby. A porter’s lodge was constructed on the higher land at the south-western end of the site alongside the arched entrance.

The 19th Century:

The cemetery was consecrated by Lord Bishop Dr Sumner in January 1829. The first interment, of John L. Harem of Slater Street, took place on June 11th 1829. The economic success of the cemetery became apparent almost immediately – by 1830 the company was paying a dividend of eight percent. The cemetery began to fill rapidly, with a peak of 2,640 burials in 1857 (around seven interments per day).

View examples of burial receipts and charges

Complaints regarding the sanitation of the cemetery rose in line with wider concerns over public health in the mid-nineteenth century. Fears over the dangers of intramural burials had existed since the previous century, but were increasing, particularly following the first cholera epidemic in 1832. Publications such as Gatherings from Graveyards (Walker 1839) and Edwin Chadwick’s public health report of 1843 drew attention to the dangers of pit burials and the urgent need for burial reforms. At St James’ Cemetery it was the practice to “pile the coffins of the poorest class in deep graves or pits, one coffin over the other, with only a thin covering of earth over each coffin until the pit is filled, when it holds upwards of thirty” (Chadwick 1843, p.139). A subsequent report by the Medical Officer of Health Dr W. M. Duncan in 1849 drew attention to the dangers of emanations from burial grounds. Of the average 10,000 or 11,000 burials in Liverpool each year, approximately two thirds were in pits. In St James’ Cemetery only six inches of soil were placed over the coffins at the end of each day, and it was urgently recommended that pit burials be ceased (Duncan 1849). A series of Burial Acts were passed from 1852, leading to the increased number of newly established garden cemeteries nationwide, but the debate over the potential hazards of St James’ Cemetery persisted throughout the second half of the century. Petitions for the closure of the cemetery circulated in 1867, with complaints over the continuance of burials despite the foundation of new cemeteries outside of the city. Local residents also complained of the unauthorised opening of new graves on the higher ground alongside Upper Duke Street (Liverpool Daily Post 1867, p.5).

Closure of the cemetery was again debated in the 1880s when the site was proposed as a location for the new cathedral in 1883. It was suggested that the cemetery be filled in and the cathedral erected above it, prompting outcries against the desecration of the cemetery. T. W. Christie wrote: “with your committee you are proposing to desecrate St. James’s Cemetery as though it were the devil’s acre, to be outraged, hacked up, filled in!” (Christie 1884, p.532)

Debate on closure continued through the 1890s, again on sanitation grounds. In 1892, the Medical Officer of Health declared that all interments in town should cease, despite the observation that burials were conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Burial Acts, pits were no longer used, and there were no dangers to public health (Liverpool Mercury 1892). Regardless, the Health Committee ruled that the cemetery stay open, as there was still room for further burials.

20th Century & Closure:

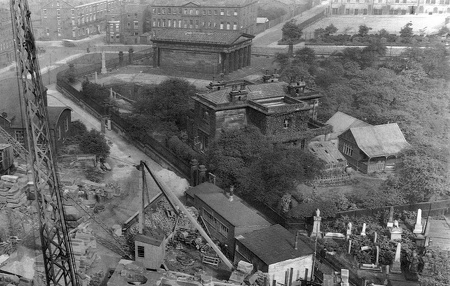

In June 1901 the site of St James’ Mount was chosen for the new cathedral, and its foundation stone was laid in 1904. In 1902 a section of cemetery land comprising of the north-western corner and western terraces was sold to the Cathedral Committee. The number of annual interments decreased gradually from the turn of the century, and as the centre of the population moved out of the city and new cemeteries were provided, the Trustees had difficulty filling vacancies. There was an understanding that after the Cathedral Committee had acquired the land, they would become Trustees of the cemetery, but after its condition and poor financial situation became apparent, this was rescinded. By the 1930s, the Trustees no longer had funds for the continued maintenance of the cemetery. Complaints about the appearance of the cemetery increased, and in 1933 a questionnaire was sent to all grave owners to assess their opinions on the future of the cemetery. The Trustees attempted to contact the approximately 5,000 grave owners to ask their preference of the following options: a) filling up the cemetery to the level of the surrounding streets, b) moving the monuments and remains to another burial ground, c) leaving the space consecrated for all time, or d) dedicating the site to the public use as a garden (Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury 1933). It was declared two years later that the cemetery would become a public garden:

The position of St. James’s Cemetery is really unique, with its many reminders of prominent Liverpool families, its bird sanctuary, and its spreading trees, all of which tend to make it a veritable oasis in the midst of a noisy city (Liverpool Daily Post 1935).

The last burial took place in July 1936, and the cemetery closed after a recorded 57,839 interments. The Liverpool Corporation Act of 1936 formalised the acquisition of the cemetery by the Corporation, with a view to maintain the site as an open space with the powers to lower, cover up, or remove memorials. The Liverpool Daily Post subsequently declared that “an awkward problem may be regarded as solved”. In 1939 a large number of memorials were removed from the Higher Western Terrace to the lower northern area of the site (below the Oratory) as construction of the Cathedral continued.

The site, however, was neglected and quickly became overgrown and in a general state of disrepair. The dangerous nature of the site and its frequentation by drug users and incidence of other unfavourable activities finally led to action being taken by the Corporation in the 1960s. The cost of maintenance of the site as it remained was considered too great, and the memorials were cleared. The majority of gravestones were stacked at the southern end of the site above the pit burials. These were covered in earth resulting in an artificial slope. Others were lined along the sides of the site and pedestrian tunnel, with only a few of the larger monuments remaining in place. The atmosphere of the former cemetery was destroyed. Curl wrote of St James’ Cemetery and the Necropolis in 2001:

It is worse than regrettable (indeed it is a local and national disgrace) that both these cemeteries have been largely cleared (of the Necropolis virtually nothing remains) and comprehensively vandalised (both officially and unofficially) by those who were obviously ignorant of the quality and significance of what they once had.

Again, the area was neglected. The oratory was restored in 1981, and opened as a sculpture gallery as part of the newly formed National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, but the rest of the site continued to deteriorate until the end of the century. In 2001 the Archbishop’s Council and the Conservation Foundation set up The Friends of St James’ Garden and since that time the Friends have played a pivotal role in the reclamation of the site. Find out how to get involved at the Facebook Group.

Further Reading:

References

An article in The Liver, 1828

A fictional "ghostly walk" published in The Porcupine 1873

Cathedral "Feathers" in the Liverpool Echo, 1932

The Cathedral Wild Birds' Sanctuary, 1932

'Bird Cameos from our Local Sanctuaries' in Mersey Vol VII, 1935

Images: